Division of Mammals

open weekdays 8am - 5pm

visitors welcome by appointment

information for visitors

phone: (505) 277-1360

fax: (505) 277-1351

museum administrator

open weekdays 8am - 5pm

visitors welcome by appointment

information for visitors

phone: (505) 277-1360

fax: (505) 277-1351

museum administrator

| Black-footed ferrets went from being abundant at the beginning of the 20th century in western North America to presumably extinct by 1979, largely due to dwindling populations of their primary prey, the prairie dog. Prairie dog burrows also provide shelter for the ferrets and a place to raise their young. Prairie dog numbers rapidly decreased due to private and public extermination programs, and the spread of sylvatic plague (the same bacterium that causes bubonic and pneumonic plague in humans). Plague not only harmed the ferrets’ prey, but also directly killed these wild mustelids. Ferrets also were challenged by deliberate extermination by farmers and ranchers, drought, and habitat destruction and conversion. All of these factors played a role in their purported extinction by the end of the 1970s (The Nature Conservancy). |

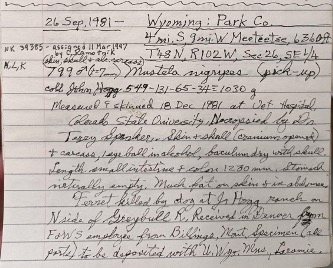

| Fortunately, on September 26, 1981, Shep, a ranch dog on the John Hogg ranch in Meeteetse, WY, killed and brought a ferret to his owners. A taxidermist realized the importance of this specimens, which led to the discovery of a small population of ferrets living on a prairie dog colony on the ranch (NPS.gov). Subsequently, these ferrets were very closely monitored and the black-footed ferret recovery program was launched. Unfortunately, the population continued to decline, resulting in a mere 18 ferrets comprising the entire population in 1987. Only seven of these individuals bred successfully and represent the founders of all ferrets alive today (The Nature Conservancy). |  The original catalog description of the specimen that led to the discovery that this species was still extant. The original catalog description of the specimen that led to the discovery that this species was still extant. |

|

Facilities involved in black-footed ferret captive breeding (FWS.gov):

|

|

Criteria for a habitat to be suitable for reintroduction (FitzRandolph, 2020):

|

|

Listing criteria: To be “downlisted” from endangered to threatened, black-footed ferrets must have 10 self-sustaining populations, and 30 to be considered recovered. Currently, 29 populations have been established but only 2 are considered self-sustaining. The rest still require supplementation because of habitat limitations and disease (Sandler et al., 2021). In total, 3,000 in the wild are needed to be considered successfully recovered (NPS.gov). |

|

A look at the numbers: Beginning in 1986, BFFs were bred in captivity and reintroduced to 29 sites across the US, Canada, and Mexico. Subsequently, over 8,000 BFFs have been produced in captivity, and around 4,100 have been reintroduced into the wild (Santymire et al., 2014). BFF’s mean lifespan is around 1 year, and up to 5 years at most (FWS.gov), however, a total of only 192 occurrences in the wild have been recorded, and of those, only 88 are specimens preserved in public museums (GBIF.org). This relatively small number means that there has been a significant loss in terms of sample preservation, data collection, fundamental research, and conservation efforts that could have been gleaned from permanently preserved specimen materials. |

|

|

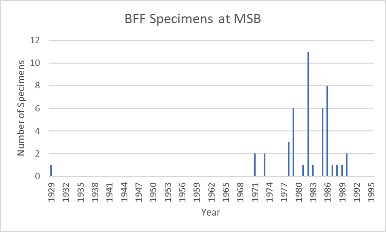

A bar graph displaying the number of black-footed ferret specimens in the MSB collection that were collected each year since 1929. Note that we have one that was collected in 1929, which is many years prior to their supposed extinction. Its genetics were likely extremely different from the others in the collection, not to mention those alive today. We have not received any collected past 1990. |

|

|

| A map of the U.S. depicting the counties from which the MSB ferret specimens were collected. If the county has a number pointing to it, that is the number of total specimens we have received from that county. If there is no number pointing to the county, we only have one ferret from there. Most are from Wyoming, though there are a few from Colorado and South Dakota, and one each from New |

|

Long-term and extensive preservation of specimens is an essential role of museums as they aim to enhance a multitude of conservation efforts through newly developed technologies. For example, recent advances have provided new methods of combatting conservation challenges such as genetic diversity loss. Because all of the black-footed ferrets alive today are products of only seven founder specimens means that this species has experienced a bottleneck that has severely reduced genetic diversity. The degree to which contemporary individuals are related to each other is between that of a sibling and a first cousin, and that close kinships leads to malformities like kinked tails and deformed sternums (Fritts, 2022). Scientists at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) were able to use cryopreserved sperm from “Scarface” and “Rocky” (both specimens are permanently archived in the MSB (skins, skeletons, and muscle tissues) to artificially inseminate females to improve levels of genetic diversity. Those two individuals were in the original population of 18 that was saved in 1987. The sperm had been stored in liquid nitrogen for as long as 20 yrs. Females that were minimally related to the donor specimens were carefully chosen (Howard et al., 2016). “Balboa” was born in 2010 from Rocky’s sperm and 8 kits have been born now in total from artificial insemination by frozen sperm. Theses subsequently reproduced naturally and slowly improved the population’s genetic diversity (Feltman, 2015). Incorporating the 8 offspring and their descendants into the captive breeding program prevented heterozygosity loss, enhanced gene diversity of the population by 0.2%, and lowered measures of inbreeding by 5.8% (Howard et al., 2016). Semen is a finite resource, though, so in 2013 the managers of that program turned to Revive & Restore, an organization focused on incorporating biotechnologies into conservation efforts (Revive & Restore). Scientists at R&R sequenced genomes of different black-footed ferrets: Balboa, a kit born from artificial insemination, and Cheerio, Cadbury, and Thorpe, the “every ferrets” representing the majority of the population. They also sequenced genomes from the cryopreserved cell lines of two specimens kept in the San Diego Frozen Zoo, a collection of frozen biomaterials, like cell cultures, oocytes, sperm, and embryos (San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, 2016). Both of the organisms that these cell lines came from, “Willa” and a specimen only known as “Studbook #2”, were part of the 18 ferrets that were rescued in 1987, but never bred successfully in captivity. That means they possess unique genetic diversity that wasn’t passed onto future generations. In comparing these genomes, they found that heterozygosity had declined 15% since the 80s and that genetic variation had declined 55%. Balboa’s heterozygosity, though, was fully recovered to historic levels, and his genetic variation improved by 25% (Revive & Restore). These discoveries promoted the idea that cloning cryopreserved cell lines was a viable route of genetic rescue. The team decided that benefits outweighed the risks (not to mention the cost of about $40,000), so R&R teamed up with ViaGen Pets (a pet cloning company) and a commercial ferret breeder to develop a plan (Fritts, 2022). Two lines of work emerged: cloning Willa’s cell line, and clearing canine distemper from the other cell line so that it can potentially be cloned too (Revive & Restore). The MSB also has the skin and skeleton of "Willa" permanently preserved for future work. The first trial began in October 2020, when the Frozen Zoo sent Willa’s cell line to ViaGen’s lab in NY. They created embryos and implanted them into 3 domestic ferret surrogates. Then, the surrogates were shipped to the National Black-footed Ferret Conservation Center in Colorado. At day 14, an ultrasound confirmed heartbeats in a single developing kit. On Dec 10 of the same year, Elizabeth Ann was delivered by C-section (Imbler, 2021). She was placed with a surrogate mother and siblings, where she often ended up on the bottom of the pile of kits. It was touch and go at first, but she made it through (Fritts, 2022). On her 65th day of life, technicians drew her blood, swabbed her cheek, and sent the samples off to a conservation geneticist at U of Florida (Imbler, 2021), who confirmed that aside from her mitochondrial DNA that came from the domestic mother, genetic analysis showed she was 100% black-footed ferret. Going forward, the plan was to mate her with a captive male, and then breed her male offspring (which would still have mitochondrial DNA) with captive females, essentially losing the traces of mitochondrial domestic ferret DNA. Genomic analysis shows that Willa’s DNA has 10x more unique alleles than any captive-bred ferret (Fritts, 2022). This marked the first native, endangered animal species in North America to be cloned (Imbler, 2021). The technique that was used to create the cloned embryo is called somatic cell nuclear transfer, and involves replacing an egg cell nucleus with a nucleus taken from a body cell, and then providing a jolt of electricity to help the egg and nucleus fuse and start multiplying. After that, the embryo is transferred to a surrogate mother (Fritts, 2022). This cloning technology did not even exist when the samples were first stored in the frozen zoo. This just goes to show the incredible outcomes that can come from long-term storage of specimens and their tissues. The preservation of Rocky and Scarface’s sperm, as well as Willa’s cell line, have proven to be phenomenal resources in terms of black-footed ferret recovery and improvement to their genetic diversity. Predicting what technologies will be available in years to come is difficult, so we must continue to improve the degree and quality of the museum specimens of all types that are collected and preserved for future research and management. |

Elizabeth Ann, the ferret kit that was cloned from Willa’s preserved cell line (Revive & Restore). |

Mustela nigripes | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (n.d.). FWS.gov.

Black-footed Ferret. (2021, October 21). The Nature Conservancy.

FitzRandolph, F. (2020, May 13). Reintroduction of the Black Footed Ferret. ArcGIS StoryMaps.

Mustela nigripes (Audubon & Bachman, 1851). (n.d.). GBIF.org. Retrieved November 28, 2022.