Conservation of Desert Wetlands and their Biotas

By Mauricio De la Maza-Benignos, Ma. de Lourdes Lozano-Vilano, and Evan W. Carson

El Pandeño Spring

El Pandeño SpringThis book is a case study of our work at El Pandeño Spring in Julimes, Chihuahua, México. This desert spring is the flagship of a larger model for conservation of desert wetlands in arid lands of México. The emphasis is on conservation of ecosystems through partnership with local landowners to ensure sustainable development of their water resources. Our strategy includes development of education workshops for local communities and schools, as well as characterization, monitoring, restoration, and improvement of aquatic habitats.

The community of farmers at El Pandeño relies on local desert springs for irrigation of crops. While El Pandeño Spring is highly modified, it maintains a remarkable suite indigenous species, including the microendemic Julimes pupfish, Cyprinodon julimes. This pupfish is the focus of conservation. How can you not admire a fish that can tolerate constant exposure to temperatures over 42˚C? Other species of focus include an endemic and a native hydrobiid snail, a possibly endemic isopod, and an undescribed endemic mosquitofish.

Andrea Cantú of Pronatura Noreste is snorkeling forCarbonera pupfish in the natural refuge at Ojo Caliente.

Andrea Cantú of Pronatura Noreste is snorkeling forCarbonera pupfish in the natural refuge at Ojo Caliente.As part of this holistic approach to biodiversity conservation, we characterized the biota of the spring and its surroundings, and initiated a program for monitoring biotic and abiotic changes in the spring. Our activities range from monitoring changes in physicochemistry of the water to monitoring changes genetic diversity and effective population size of pupfish. Through our partnership with Amigos del Pandeño, we restored a former marsh and the population of pupfish expanded as a result. In 2014, the site was declared a Wetland of International Importance under the RAMSAR Convention and also was recognized on President of Mexico's website. We are very pleased with the conservation success achieved at Julimes.

El Pandeño and Beyond

Model Systems

Crops irrigated by waters from El Pandeño Spring

Crops irrigated by waters from El Pandeño SpringA holistic approach in which conservation is achieved through working directly with landowners is often necessary. In many areas, standard approaches simply aren’t feasible or effective.

Our model is built on intense conservation efforts at a few sites, which, together, represent several of the more pressing challenges in conservation of arid land ecosystems, and in biodiversity conservation generally. For example, at Julimes (El Pandeño) we work with local farmers and focus conservation efforts on sustainable use of water, monitoring of springs as indicators of sustainable use, and restoration of degraded habitats. At San Diego de Alcalá, a desert-spring complex near Julimes, we take a more hands-off approach. Here, agreements with a local landowner focus on protection of a largely intact desert spring ecosystem while meeting the landowners needs for development of recreational opportunities on the property. Finally, at Ejido Rancho Nuevo, we are working with this community to protect the last remaining spring on the property, the critically imperiled Ojo Solo. As part of this project, at the nearby Ejido Villa Ahumada y Anexos, we established a natural-refuge for the endemic Carbonera pupfish Cyprinodon fontinalis.

Translocation of endangered species to Ojo Caliente.

Translocation of endangered species to Ojo Caliente.

Pictured are Mauricio De la Maza-Benignos (left), who is the

Conservation Director at Pronatura Noreste, and Evan W.

Carson (right).In addition to these primary sites, we conduct lower level monitoring and population surveys of habitats and species in other areas throughout Chihuahua. This work includes habitats of all described pupfishes of the state. These habitats vary in their ownership (e.g., private, ejido, and municipal), as well as the threats they face (e.g., from agriculture, recreation, and pollution).

Accomplishments

We restored and expanded marsh habitats at El Pandeño and created a natural refuge at Ojo Caliente. The population of Carbonera pupfish is thriving in the refuge.

Over the last few years, we rediscovered two species that were considered extinct under the IUCN Red List of threatened species- a hydrobiid snail at El Pandeño, Tryonia julimesensis, and the Chihuahuan Dwarf Crayfish, Cambarellus chihuahuae. We also found new records for other hydrobiid snails, including at least one that is an undescribed species at Ojo Solo.

Our work has been successful in large part because our partnerships with local landowners have been successful.

This work is supported by several recent grants, including one from the Desert Fishes Council to create the refuge at Ojo Caliente, to one from The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund to conduct habitat and genetic monitoring at Ojo Caliente and Ojo Solo, and to conduct educational workshops in the local ejido communities.

Findings from this work are not gathering dust, either. Information is available through dissemination in the primary literature, publication of conservation action and monitoring plans, and through publication of works such as the Julimes Case study. Making this information known and available freely is of great importance to conservation.

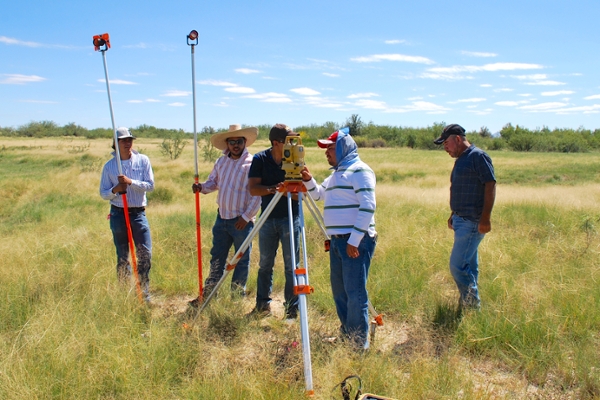

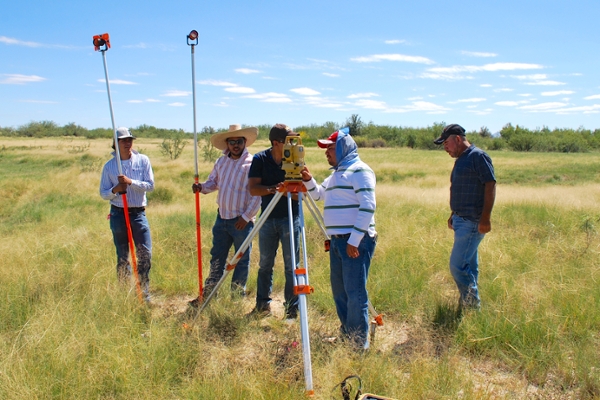

Survey work prior to creation of the natural refuge at OjoCaliente.

Survey work prior to creation of the natural refuge at OjoCaliente. The critically endangered Chihuahuan Dwarf Crayfish, whichwas presumed extinct until we rediscovered it at Ojo Solo inin September 2012

The critically endangered Chihuahuan Dwarf Crayfish, whichwas presumed extinct until we rediscovered it at Ojo Solo inin September 2012Challenges

Wetland ecosystems of desert areas of Mexico and the southwestern US are under immense pressure from groundwater extraction and other unsustainable activities that exploit water resources in the region. Climate change is expected to exacerbate these pressures, while socio-economic conditions are important today and will remain so, especially since many human communities in the area are impoverished. From a conservation standpoint, long-term prospects for management depend in part on viability of human communities. Even at sites where we regularly monitor, there is great concern about extinction. Across the larger landscape, many habitats and species continue to disappear- some without being known to science. We are working to prevent the extinction of critically imperiled species such as the bigmouth shiner Cyprinella bocagrande and Chihuahuan Dwarf Crayfish Cambarellus chihuahuae. For the crayfish, we are working with experts in crayfish aquaculture to bring the species into captivity and buy time before a suitable natural-refuge can be established.

Outlook

An irrigation canal that was modified to reduce water wasteand ensure sustainable development of water resourcesat El Pandeño.

An irrigation canal that was modified to reduce water wasteand ensure sustainable development of water resourcesat El Pandeño.We are cautiously optimistic about continued success of our projects and how these model systems may aid conservation more broadly. We have had success in restoring habitats, such as the marsh at Julimes, and in building a natural refuge for the Critically endangered Carbonera pupfish. We are hopeful about new opportunities to bring crayfish into captivity until we can establish a refuge for this endangered invertebrate. While we know that many systems and species will be lost, we can’t know which ones, and we can prevent some from meeting this fate. One must never give up!

Collaboration

Environmental monitoring at the restored marsh habitat in ElPandeño. Pictured are Mauricio De la Maza-Benignos (left)and Lissette Sepúlveda (middle) of Pronatura Noreste.

Environmental monitoring at the restored marsh habitat in ElPandeño. Pictured are Mauricio De la Maza-Benignos (left)and Lissette Sepúlveda (middle) of Pronatura Noreste.This project is led by Pronatura Noreste (a Mexican conservation NGO) and involves scientists from Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, as well as myself. From the UNM side, the MSB and LAII have provided invaluable support by helping to disseminate information about the project. For example, the book is available free as a downloadable PDF in the MSB, LAII, and Biology Dept. collections in LoboVault. Seminar opportunities and outlets such as that at the MSB website also are important. This support feeds back to Mexico, where my colleagues at PNE and UANL earn support from the international recognition their important work. It’s win-win-win for conservation, México, and NM!

International Exchange Program

A major goal is to develop an international student-exchange program between Mexican universities and UNM. The idea is to help bridge the political boundaries that hamper conservation of the species and habitats that do not recognize such boundaries. UNM is a superb place for this to be launched. There is a deep history of Hispanic culture and influence in NM, with important ties to Mexico in particular. A main focus of this program is building a legacy conservation and aquatic science in northern Mexico. It is critical to build capacity and increase the number of scientists working in northern Mexico but also to train scientists who are from northern Mexico.

The MSB

Translocation of Carbonera Pupfish to the natural refuge at Ojo Caliente. Pictured are Evan W. Carson (left) and MauricioDe la Maza-Benignos (right).

Translocation of Carbonera Pupfish to the natural refuge at Ojo Caliente. Pictured are Evan W. Carson (left) and MauricioDe la Maza-Benignos (right).The role of collections and museum-based studies is critical to our work. For example, collections and curators have played important roles in helping us document new species and new records for described species. With tiny organisms, such as most hydrobiid snails, when identification is needed there is no replacement for vouchered (or vouchering of!) specimens. In the case of the Chihuahuan Dwarf Crayfish, verification of the species was based in part on vouchered specimens. In areas we work, many habitats have changed over time, and understanding how the fauna has changed - morphologically, ecologically, genetically - can require access to museum specimens because these may be the only source for comparison over time. One of our goals is to facilitate partnership between museums in Mexico and the US - UNM in particular - so that these invaluable museum collections are used to their greatest potential and, in turn, do not decline from lack of institutional and other support.

Related Links

Conservation of Desert Wetlands and Their Biotas is available as a PDF download. See also the website for Amigos del Pandeño, the NGO established by the farmer community.

Construction of the Carbonera Pupfish refuge habitat was funded by the Desert Fishes Council. The Final Report is on Evan Carson’s website.

In 2014, Julimes was declared a Wetland of International Importance under the RAMSAR Convention, an accomplishment that was profiled on the website of the President of México (link in Spanish)

Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund funded the first year of monitoring for the Carbonera Pupfish project.

Pronatura Noreste A.C. is the Mexican NGO that brought these projects together. Main collaborators were Mauricio De la Maza-Benignos of Pronatura Noreste and Lourdes Lozano-Vilano of Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.